What Two Data Elements Should Be Reported Because A Referral Is Involved

- Research article

- Open Access

- Published:

Full general practitioners referring patients to specialists in tertiary healthcare: a qualitative study

BMC Family unit Practice volume twenty, Article number:165 (2019) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

There is a large and unexplained variation in referral rates to specialists by general practitioners, which calls for investigations regarding general practitioners' perceptions and expectations during the referral process. Our objective was to draw the conclusion-making process underlying referral of patients to specialists by general practitioners working in a university outpatient primary intendance heart.

Methods

Two focus groups were conducted amidst full general practitioners (x residents and viii chief residents) working in the Center for Chief Care and Public Health (Unisanté) of the University of Lausanne, in Switzerland. Focus group information were analyzed with thematic content analysis. A feedback group of general practitioners validated the results.

Results

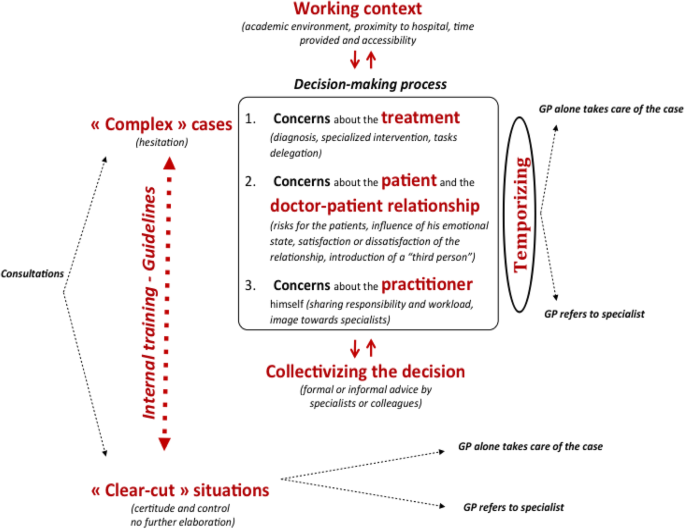

Participating general practitioners distinguished 2 kinds of situations regarding referral: a) "articulate-cut situations", in which the decision to refer or not seems obvious and b) "circuitous cases", in which they hesitate to refer or not. Regarding the "complex cases", they reported diverse types of concerns: a) well-nigh the handling, b) nearly the patient and the doctor-patient human relationship and c) about themselves. General practitioners evoked numerous reasons for referring, including non-medical factors such equally influencing patients' emotions, earning specialists' esteem or sharing responsibility. They too explained that they seek validation by colleagues and postpone referral and so as to relieve some of the decision-related distress.

Conclusions

General practitioners' referral of patients to specialists cannot be explained in biomedical terms only. It seems necessary to take into account the fact that referral is a sensitive topic for full general practitioners, involving emotionally charged interactions and relationships with patients, colleagues, specialists and supervisors. The conclusion to refer or not is influenced by multiple contextual, personal and clinical factors that dynamically interact and shape the decision-making process.

Groundwork

General practitioners' (GPs') referral to specialists has legal and upstanding dimensions, as inadequate referral tin seriously undermine the quality of care [ane,2,3]. Yet, GPs' referral practices take yet not been comprehensively investigated, even if they are performed routinely. There is a significant and multifactorial variation in GPs' referral rates to specialists. This variation remains largely unexplained, as less than half of it can be linked to patient, practice or GP factors [4,5,6]. Studies focusing on the referral process are therefore profoundly needed, [5] notably qualitative studies providing new insights and hypotheses regarding how GPs are experiencing and conducting this process [iii, vii]. Such studies seem especially important since there might be a gap between the lived reality of the referral process and its theoretical or authoritative depictions, specially with respect to the GPs' concerns, feelings and attitudes [8].

These issues are particularly important in the Swiss healthcare system. In Switzerland, health insurers advantage patients for seeing a GP before consulting a specialist (37% of patients' insurances) [ix]. This context creates an equivalent to the gatekeeping system, [9] 67% of the population seeing a GP at to the lowest degree one time a year (36% consult a specialist on their ain initiative during the same period) [10]. One of Swiss patients' main expectations towards GPs is an adequate coordination of care [11]. GPs' essential role in the coordination of healthcare is widely proven, especially for the chronically and "complex" patients [1, 12]. On the contrary, inadequate referral tin undermine the quality of care and lead to the misuse of resources [3, 13,14,15,16]. While Swiss GPs resolve 94.three% of all problems encountered, a specialist referral charge per unit of 9.44% has recently been reported. This is three times as much as information technology was in 1989, but similar to rates measured elsewhere, notably in the USA [1, 17]. The "prescription" of a specialized intervention has thus get a daily activity of Swiss GPs.

The aim of this report is to contribute to a better understanding of the referral procedure by investigating what leads GPs to initiate or non a referral [18]. More precisely, we have tried to identify the factors that GPs working in a Swiss university dispensary consider when pondering whether they should refer a patient to a specialist. Indeed, to the best of our knowledge, no qualitative inquiry has studied the referral process from the bespeak of view of GPs, nor questioned their experiences and preoccupations related to referral.

Methods

The study, conducted at the Center for General Medicine (CGM) of the Academy of Lausanne, in Switzerland, took place between Dec 2016 and June 2017, post-obit approval by the Cantonal Ideals Committee for Research on Human being Beings (CER-VD). The CGM is part of the Center for Primary Intendance and Public Health (Unisanté), proposing primary health care to Lausanne'south general population (a population of 400′000). Patients visit the CGM for whatsoever health-related problem, either later on an appointment or as an emergency. CGM GPs offer showtime-line treatments and follow-ups. Located besides the Lausanne Academy Hospital, CGM directly collaborates with its specialists and then every bit to provide coordinated outpatient primary care. It is also engaged in continuous collaborations with specialists in nearby individual practices. The CGM is a referral centre for internal and general medicine and the but academy center preparation futurity GPs for the surrounding expanse. It is equanimous of 40 GPs (residents and master residents). During 2017, CGM GPs conducted more than 18′000 consultations and followed upwards four′000 patients. Nearly twoscore% of consulting patients accept psychosocial vulnerabilities [19]. These item features should be kept in mind in order to avoid overgeneralizing of our results. Furthermore, the fact that well-nigh GPs participating in our study are immature clinicians, usually still in grooming, tin can accept an upshot on the way they refer to specialists and experience the referral process.

The first step of our enquiry program was to ensure that our setting was appropriate for observing and investigating the referral process. We created a questionnaire on referral, based to the existing literature, and conducted a survey among CCM GPs in order to compare the existing literature findings with the studied population. Our survey'southward results (N = 31) showed that in the CGM setting, the referral process is significantly important, being principally conducted past the residents. This makes the CGM a suitable setting for observing the referral process. The questionnaire'south results were used to develop the questions of the Focus Groups' (FGs') moderator'south guide (see Additional file i).

A showtime FG was conducted with residents [20,21,22]. The last writer (FS) with extensive experience in conducting FGs acted as moderator. To have a more consummate view of the studied phenomenon, a FG was conducted with chief residents. The basic hypothesis underlying the choice to distinguish between residents and chief residents was that seniority, status, and decisional power could have an effect on referral and on GPs' experience of the referral process (unlike roles, levels of responsibility within the CGM, clinical experiences, etc.) [23, 24].

The FGs were audio recorded and the principal investigator transcribed them manually. The transcripts were analyzed by means of a qualitative approach. The two principal investigators, a consultation-liaison psychiatrist (KT) and a social scientist (PNO), independently conducted a thematic content assay on the transcribed FGs, with a specific focus on GPs' self-reported concerns about the referral procedure and conclusion [22, 25, 26]. A deductive-inductive approach was used during coding. Based on the questionnaire's results, the two main investigators agreed on an "a priori" analytical framework specifying key themes and questions. They so transformed this framework during analysis when information technology revealed inadequate to deal with the data [27]. The analysis was conducted independently past the 2 main investigators, which resulted in 2 slightly different sets of codes. They and so confronted their findings and created an analytical model describing the master features of GPs' decision-making process during referral.

At this point, the ongoing analysis was discussed with the other investigators. This discussion made clear that the ii main investigators had been too focused on the decision-making process, setting autonomously other elements ("tactics" and referral "facilitators", come across below). The ii main investigators reviewed again the transcripts independently, taking intendance to include these aspects they had previously left out. A dynamic model was developed, accounting for participating GPs' distinction between what they run across as "lucent" and "complex" situations and identifying stress-reducing "tactics" used by GPs as well as what they encounter every bit referral "facilitators". The other investigators validated these results.

During the data processing stage, equally well as during the information analysis and interpretation stage, the emerging themes were submitted to a feedback group of CGM-GPs. The developed "model" of the referral process was besides submitted to this group. We went dorsum and forth until we confirmed that our interpretations were going in the right direction. Triangulation of methods and respondents' validation increased the validity of our study.

Results

Ten residents participated in the commencement FG and eight chief residents to the second FG.

"Clear-cut situations" versus "circuitous cases"

During the FGs, GPs distinguished 2 types of situations regarding the referral process: 1) "lucent situations" and ii) "circuitous cases". They expressed the feeling that some cases need no further thoughts. Facing such "articulate-cut situations", GPs reported that they practise non hesitate:

"In that location are situations in which it is very clear that nosotros need a specialist. For example, we have a patient with typical, uh… chest pain. Or even atypical, but who has risk factors, so we say to ourselves that we tin't waste product fourth dimension and nosotros must exclude the cardiac origin. So it seems pretty obvious that you lot need a stress exam…"

Participating GPs said that these "clear-cutting situations" are rare in their current working context, just occur much more than oftentimes in private practices or in secondary care centers:

"When you're doing an internship in a GP's office… I was in the countryside… We saw many more than patients a day than here, merely then they were much 'simpler'. […] The betoken is, referring or non is oft clearer with 'simple' patients."

Indeed, they believe that they encounter many "complex cases" at the CGM. "Complexity" here doesn't hateful that the intervention of a specialist is needed, only that it is difficult for GPs to decide if such intervention is necessary or whether information technology would be beneficial. When GPs are confronted with these situations, they often feel lost, not knowing how to go on:

"Nosotros have complex patients who have a lot of comorbidities and treatments; and sometimes managing high blood pressure for case... 1 tells oneself: 'But now I don't know what to exercise… Maybe I should take the specialists requite me some advice.'"

Emotionally, "articulate-cut" situations" and "complex cases" accept contrasting significances. On the one hand, cases in which the conclusion to refer is difficult to make are linked by GPs to stress and anxiety. On the other manus, cases in which referring or not is "obvious" tin can give them the feeling of being "nothing more" than "sorter physicians":

"[…] writing referral demands, eventually it becomes really frustrating and I think that it's… If what's expected of a GP is beingness a 'sorter medico', in that location won't be many candidates for our profession…"

Such remarks reveal that referring is very significant for GPs with regard to how they perceive themselves, as opposed to specialists.

Controlling facing "complex cases"

Participating GPs reported that the decision to refer or not can be multi-layered, multifactorial and thus quite difficult to make in the "complex cases". They attempt to continuously maintain a delicate remainder betwixt the "quality" and "safety" of care, taking into account the possible drawbacks of referrals:

"This is exactly the betoken regarding the notion of gatekeeping, which is really a delicate rest between quality and security of care. And then if nosotros are chosen to act as gatekeepers, to what extent are we supposed to do it or not?"

More chiefly, our study reveals that GPs entertain diverse concerns regarding cases in which they hesitate to refer. These concerns can be classified into iii different categories: a) concerns about the treatment, b) concerns nearly the patient and the medico-patient relationship and c) concerns about the referring GP himself.

A) Regarding the concerns about the handling, participating GPs indicated that they plough to specialists to optimize medical care when confronted with their own limits (theoretical, clinical or applied). In such cases, they refer to specialists for specific examinations or procedures they tin can't or aren't confident to do by themselves:

"Referring likewise brings security… Confidence… When nosotros have some data, guidelines, only aren't experts […]. Even when nosotros go and expect into the existing literature, we are never sure that we have the concluding guidelines…"

However, GPs also stated that they sometimes utilise referrals to delegate tasks to specialists in order to concentrate on other aspects of treatment. In such cases, they seem to use referrals in an "instrumental manner" to salvage consultation fourth dimension that they want to apply differently, creating a specific division of labor between themselves and the specialists:

"One time a program of care has been established and some of the problems are handled [by the specialist], nosotros can make fourth dimension for more psychological, social, personal matters… Er… It'due south a way to move frontwards…"

B) The second set of concerns regards the consequences of referring for the patient and for the doctor-patient relationship. GPs notably reported being quite preoccupied with the financial and/or psychological "cost" of referrals, specially in the case of the more than vulnerable patients:

"For some of my patients, there has been no advantage at all [in the referral]. It was terribly stressful for them … Often, they don't understand French and some specialists don't ask for a translator to be present, even when we mention it on our request… They aren't explained anything, and… They come dorsum to u.s., and we take to explain what the specialist reported…"

Participating GPs said they therefore see the explicit demands of patients with some circumspection, since seeing a specialist could influence the patient'southward emotional state even positively or negatively, depending on the specialist-patient human relationship:

"It depends on the contact they accept with the specialist… There are patients who come back very upset considering they have not been explained annihilation (Thou: Yes). While in that location... at that place are other times they come dorsum with stars in their eyes, as if they had a revelation. […] That'southward right, it depends a lot on how consultation happens…"

Participating GPs – especially chief residents – too expressed concern about the possible effects of referrals on their relationship with the patient. On the one paw, they said they worry that patients would be disappointed if they didn't agree to let them run across a specialist. On the other hand, they evoked that they sometimes fear that referring could undermine the patient's confidence in their judgement, or that meeting a specialist would prompt patients to compare their respective cognition and skills:

"When nosotros decide to refer or non, information technology is often difficult to know if we are doing too much or not enough. If we inquire for advice all the time, the patient may feel insecure, considering [he may retrieve:] 'Hell, this doc is insecure!' Just if we determine not to refer, [he may think:] 'This dr. does nothing only look some more."

Considering these diverse aspects, GPs expressed the feeling that referring means adding a "tertiary political party" to the "dyadic" doctor-patient relationship, which inevitably changes the relationship'south balance and dynamics. This fact is considered by GPs before referring:

"The issue of the relationship of class, nosotros have… A dyadic human relationship between physician and patient, which can be stable or non, only if nosotros… We add a tertiary contributor, the human relationship won't be dyadic anymore. Then it's very important to know why this third contributor is necessary. […] Because of course, if something goes wrong between the patient and the specialist, it will necessarily impact the relationship between the patient and the family physician."

C) A third set of concerns regards the possible consequences of the referral for GPs themselves. Indeed, GPs mentioned the wish to share responsibility in order to be legally "covered" or to accommodate to institutional expectations:

"But nosotros tell ourselves that we are still obliged to cover ourselves. If tomorrow a patient leaves and we miss something, information technology will be in the newspapers and and then information technology can get bigger and bigger… If we make a mistake it's a bit of a disaster, and… Peculiarly as we're in an academic institution…"

These factors are evoked past GPs equally prompting them to refer. Nevertheless, they also limited the fear that unnecessary or too numerous referrals might be taken every bit a sign of incompetence by specialists, patients, colleagues or supervisors. It seems of import for GPs' self-esteem to feel and demonstrate to others that they are able to manage things "on their own":

"Or narcissism… I hateful, yeah: 'I can do it! Why wouldn't I do past myself?' […] 'Yeah, I'll read on the weekend, and I'll do it."

Viewed as such, abnegation from referring can be experienced as a "challenge" to be taken up, especially as CGM-GPs reported they feel some sort of latent contest with specialists.

"Tactics"

Participating GPs also addressed the ways they effort to relieve the decision-related distress experienced in "complex cases". We describe such behavior as "tactics", i.due east. attempts to make a state of affairs easier to confront without radically altering it. They reported using ii distinct "tactics" when hesitating to refer or non: a) seeking advice of colleagues (specialists or GPs) and b) postponing the referral and adopting a "watchful waiting" approach.

A) Regarding the first, GPs indicated that they oftentimes go advice before referring, either by soliciting the informal opinion of a specialist they personally know, or in a more than formal manner by requesting assistance from their supervisor. Such interactions assist them to better comprehend the case at pale just by describing it to someone else:

"I also ofttimes talk with my colleague from the next office considering… If it'south a situation where I'm stuck a piffling bit, if I'm non very sure whether I should refer or not, it will give me the opportunity to summarize the situation orally to somebody. Well, sometimes information technology helps to see things more than conspicuously…"

In addition, participating residents emphasized their supervisor's influence on their decisions regarding referrals.

B) Every bit to the second "tactic", the use of "watchful waiting", GPs indicated that they sometimes cull to postpone referring when they hesitate:

"And and then at that place is the question of time, too. Tin can nosotros expect a little longer before sending to the specialist? Try other treatments, err..."

Of course, GPs reported that they use such "tactic" only in "not-emergency" cases. Eventually, emerges the question of how long tin the referral conclusion be postponed.

Referral "facilitators"

Participating GPs mentioned various factors that facilitate the referral procedure, namely a) internal training, b) guidelines, and the c) availability of colleagues, specialists and/or supervisors.

A) GPs expressed that internal training has an important affect on their referring practices, as it can pb them to handle sure situations with much more confidence and/or without the help or advice of a specialist.

"We likewise have training. For example, lately there has been a symposium on gastroenterology well-nigh what to practise in healthy adult in gastroenterology, so it allows us not to send anybody to gastroscopy… [M: Internal training] Yes, which is really suitable for generalists."

B) GPs expressed the need to rely on clear theoretical backgrounds when referring, with guidelines being perceived as supporting and facilitating referral decisions. All the same, participating GPs' attitudes towards guidelines are more ambiguous, as they consider guidelines as "forcing" some referrals that could accept been avoided. In this perspective, guidelines announced as an institutional force per unit area rather than as a decision back up tool:

"And then there is the question of guidelines. Sometimes we are quite certain virtually the psychosomatic origin [of the patient's symptoms], but we say to ourselves: 'theoretically, we should yet send him to a specialist'…"

C) Finally, chief residents evoked the availability of specialists and the quality of their human relationship with them every bit important for the referral process. They regretted not benefiting plenty from more than proximity with the specialists:

"[…] with a network of specialists, knowing each other, knowing the specialists we work with. We would have a contact that would be dissimilar, information technology would be easier to ask for advice."

They underlined that personal relationships with specialists facilitate the referral process and tin can help them in their controlling.

Discussion

Summary

The aim of this report was to contribute to a more accurate agreement of how GPs decide to refer their patients to specialists [three, six, seven, eighteen]. To this finish, nosotros analyzed 2 FGs conducted amongst GPs (residents and chief residents) working in a academy outpatient clinic, located besides the Lausanne University Hospital. Nearly GPs participating in our report were immature clinicians, more than one-half of them withal in residency training. An of import number of patients visiting the clinic have psychosocial vulnerabilities. These are the specific features of our study's setting. When asked nearly what comes into play during the referral decision, participating GPs distinguished between "clear-cut situations" and "complex cases". They remember that "articulate-cut situations" are less common in their working context compared to other healthcare settings. Nevertheless, they believe that internal guidelines and training help them to feel more confident when deciding to refer or non.

Regarding the "complex cases" in which the decision to refer or non is more hard to make, GPs reported various concerns: a) about the treatment, b) about the patient and the doctor-patient relationship and c) almost themselves. The beginning set of concerns address the event of acceptable handling and optimal coordination of intendance. The decision to refer is mainly motivated by the notion that the specialist knows and/or tin can exercise more for the problem at stake. GPs too reported that they sometimes employ referrals in an instrumental way, in order to proceeds fourth dimension and room for focusing on other aspects of the patient. Regarding the possible consequences of referral for the patient and for the medico-patient relationship, GPs showed concern over the financial and/or psychological "cost" for patients. They also expressed ambivalent feelings concerning the possible effects of referrals on the medico-patient human relationship, with the specialist intruding equally a "3rd party" in their "dyadic" human relationship with the patient. Finally, participating GPs underlined that they are at times concerned for themselves and associate referral with the desire to be legally "covered" or to meet institutional expectations and with the fear of specialists', patients', colleagues and/or supervisors' judgments regarding their decisions.

Participating GPs reported that they attenuate the decision-related distress linked to some of the "circuitous cases" by a) asking colleagues (specialists or GPs) or supervisors for communication and b) postponing the referral (temporizing). The main contextual factors influencing the referral procedure were a) internal preparation, b) guidelines, and c) access to colleagues, specialists and/or supervisors.

Effigy 1 below summarizes these findings. It should not be understood equally an "objective" depiction of the referral process, only as a representation of GPs' lived experience of the referral process (Fig. ane).

The Referral Process as experienced by general practitioners

Strengths and limitations

Although the need for qualitative studies addressing the referral procedure has been acknowledged, [3, seven, 14] picayune research has been conducted so far. Our study contributes to the effort to arroyo qualitatively such a miracle, past investigating CGM GPs' expectations, thoughts, feelings and concerns when referring patients to specialists. The study thus allowed to shed low-cal on what clinicians experience and accept into business relationship when deciding whether they should refer patients to specialists or non.

Nevertheless, at that place are three obvious limitations to our study. First, the perspective nosotros have chosen is full general: nosotros did not address one specific blazon of referral, since referrals to various specialties (due east.g. psychiatry, cardiology, orthopedics, etc.) may present specific challenges. However, we experience our choice was warranted for at least two reasons: a) we wished to place some general, basic assumptions about the referral process, [eight] particularly in its theoretical depictions, which presume that the factors affecting the referral decision are purely biomedical; b) participating GPs themselves seemed to confirm that "referral" could be addressed as a unitary category. Second, our purpose being to document GPs' points of view and experiences about the referral process, we did not interview patients, specialists, or supervisors. Their inclusion would certainly add to the understanding of the referral process.

A third limitation of this study results from the specificity of the setting. All the same, the particularities of our study'southward setting are consequent with the aim of our study, and represent to a typical setting in which multiple reasons for referral be: the CGM is a academy outpatient primary care clinic face-to-face with a university hospital, in which GPs are confronted to circuitous clinical cases and work in constant collaboration with dissimilar specialists. In add-on, the CGM treats patients with psychosocial vulnerabilities, in need of multidisciplinary care, who are usually emotionally challenging for GPs [ane, 12, 28]. In such a setting, referring to specialists is a cardinal human activity in providing medical intendance and strongly preoccupies GPs, a condition that was seen as an advantage for investigating the referral process. In add-on, the bulk of participating GPs were in preparation or at an early phase of their career. Nosotros can hypothesize that young GPs with less clinical experience are more preoccupied well-nigh how to refer or non to specialists, and that therefore also diverse physician-related reasons for referral were prevalent. Appropriately, our setting was a very fertile ground for studying the referral process.

Comparison with existing literature

The bug linked to the referral process phone call for models which optimize care past facilitating "adjustment" of referral attitudes between GPs and specialists [one]. Such models should exist based on healthcare workers' expectations, experiences and affects and on qualitative studies that offering a better agreement of referral [3, half dozen, 12, 18, 29,30,31]. By focusing on GPs lived feel, our report contributes to this effort. It provides a new perspective on the referral procedure and the associated determination making process, equally nigh researchers take so far addressed this issue past solely scrutinizing the biomedical factors that influence referral.

The chief themes tackled by prior studies focusing on referral are: a) GPs' need for a improve access to specialists [12, 32]; b) importance of suitable communication and good relationships between GPs and specialists [ii, 4, 12, 15, 32,33,34,35]; c) furnishings of referral on the md-patient relationship [ii, 30, 32, 36, 37]; d) referral and heavy workload (resistance, transfer of responsibility, lack of specific training on how to "prioritize") [two, 24, 30, 32, 37]; e) uncertainty linked to referral [4, v, 24, 30]. These themes match our own results. Participating GPs evoked that they oftentimes struggle to make up one's mind whether or not they should refer patients to specialists, and that they ask colleagues for communication and/or postpone their decision. Furthermore, they expressed the wish for a better access to and relationship with specialists and presented specialists' availability as facilitating element of the referral process. They also explained that they sometimes see referral as a way to share responsibility with specialists in guild to be legally "covered", to consul tasks to specialists and to take advantage of their specific knowledge. The influence of referrals on the doctor-patient human relationship has also been widely reported past CGM GPs in the FGs.

Nevertheless, some aspects discussed in other studies don't appear in our results, such every bit the "unrealistic" character of GPs' expectations [13, 14] and their feelings of inferiority towards specialists [38, 39]. This is inappreciably surprising, as these elements tend to negatively depict GPs involvement in the referral process. In a similar style, it is worth noting that participating GPs didn't explicitly call for an improvement of principal healthcare structures or for a more intensive patients' interest in the referral process, as described in the literature [1, three, 30].

Globally, our enquiry replicates the results of prior studies, merely takes them a step further by expanding our knowledge of GPs' experience of the referral process. Aspects that oasis't been described by previous studies include: the influence of patients' emotions and specialists' esteem towards GPs; GPs' fears surrounding the issue of responsibleness; the use of referral as a way to larn from specialists; and the desire for more training, guidelines and colleagues' back up regarding the referral process. Indeed, referral appears to exist a key event for GPs, which can produce various and sometimes potent emotional states. By investigating GP's point of view of how interactions with patients, specialists and supervisors influence referring, nosotros offer a deeper knowledge of the central issues surrounding this "prescription" [38]. Finally even so importantly, nosotros also certificate some GPs' self-reported "tactics" when facing complex referral situations.

Implications for enquiry and practice

Shedding light on the referral procedure is useful: a) for GPs, b) for healthcare systems planners and c) for university medical trainers. Beingness aware of thoughts, experiences and feelings associated with the referral process increases GPs' optimal utilization of specialized care and positively influences the run a risk-do good residual of referral [12, 18, twoscore, 41]. Strategies for reducing medical over−/underuse include GPs adopting a well-founded "expect-and-meet" approach, [30] a better management of uncertainty [4, 5, 24] and a capacity of mobilizing formal or breezy information in their working environment [7, 29]. The bug surrounding the referral procedure must be taken seriously into account by healthcare organisation planners, notably with regard to effective communication and coordination between participants and the creation of efficient healthcare networks [1, 3, 7, 12, 29, 42]. Finally, university GPs expect from their supervisors that they establish specific grooming and internal guidelines for referral, adapted to their specific working context [ane, 29]. Therefore, medical trainers have to be aware of the multilayered interactions involved in the referral process [1, iii, 5]. Their clinical teaching should thus also focus on relationships and interactions in the referral process: a) the medico-patient relationship; b) the GP-specialists relationship and c) the GP-institution relationship [38, 42,43,44].

Decision

We have tried to identify more accurately the diverse grounds on which GPs decide to refer their patients to specialists, which is a central issue not merely for GPs, just too for their patients, trainers, supervisors and healthcare planners [three, vi, 12, 29]. Our study reveals that diverse factors are associated with referral. At that place are certainly biomedical elements influencing the referral procedure, but well-nigh elements are associated with the GPs' lived experiences, such as his own concerns, expectations and emotions or the perception of the patients' psychological needs, and contextual factors, [16] such as training opportunities to address the referral process. Information technology seems especially important to take into business relationship the ascertainment that referral can exist a stressful feel for the practitioner himself, challenging his self-esteem and involving problems of recognition [4, 38, 45]. Since referral is a cornerstone of interactions amongst GPs, their patients, specialists and their supervisors, its optimal direction is crucial [1, 11, 45, 46]. The various themes emerging from our research and the proposed conceptual model that organizes them contributes to a more comprehensive agreement of the referral process.

Availability of information and materials

The raw information supporting our findings is available from the Damsel Digital Repository and tin can be found in https://datadryad.org/stash/share/762cHyghHxTUTTKFeVxPLMbdLipYbB4JXz-9wYPjFS0

Abbreviations

- CER-VD:

-

Cantonal Commission on Ethics for Research on Man Beings

- CGM:

-

Eye for Full general Medicine

- FGs:

-

Focus Groups

- FLHR:

-

Federal Law on Human Research

- GPs:

-

General practitioners

References

-

Kringos DS, Boerma WGW, Hutchinson A, Saltman RB. Building primary Intendance in a Changing Europe. The European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, observatory studies series 38 (2015). Eur Psychiatry. 2016;33:18–36.

-

Piterman L, Koritsas S. General practitioner–specialist referral procedure. Intern Med J. 2005;35:491–6.

-

Winpenny EM, Miani C, Pitchforth E, et al. Improving the effectiveness and efficiency of outpatient services: a scoping review of interventions at the master–secondary care interface. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2016;0(0):ane–12.

-

O'Donnell CA. Variation in GP referral rates: what tin we learn from the literature? Fam Pract. 2000;17(half dozen):462–71.

-

Ringberg U, Fleten Due north, Førde OH. Examining the variation in GPs' referral practice: a crosssectional report of GPs' reasons for referral. Br J Gen Pract. 2014;64(624):426–33.

-

Sullivan CO, Omar RZ, Ambler Chiliad, Majeed A. Case-mix and variation in specialist referrals in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(516):529–33.

-

Zwarenstein M, Goldman J, Reeves S. Interprofessional collaboration: effects of practise-based interventions on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;four:one–29.

-

Chew-Graham C, Slade M, Montana C, et al. A qualitative study of referral to community mental health teams in the U.k.: exploring the rhetoric and the reality. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7(117):1–9.

-

Senn N, Ebert ST, Cohidon C. La médecine de famille en Suisse - analyse et perspectives Sur la base des indicateurs du programme SPAM (Swiss master care active monitoring), OBSAN (Swiss health observatory) 2016;11(55):1-4. French.

-

Storni One thousand, Kaeser M, Lieberherr R. Enquête Suisse sur la santé 2012. Vue d'ensemble. Office Fédéral de la statistique. Neuchâtel 2013;Santé 14/213-1202:i-31. French.

-

Droz Yard, Cohidon C, Senn N. Patients' values regarding family medicine in Switzerland. Transitions, SGAIM/SSMIG/SSGIM, 1ère Assemblée de printemps 2016;P435.

-

Mitchell GK, Burridge 50, Zhang J, et al. Systematic review of integrated models of health care deliver at the chief- secondary interface: how constructive is information technology and what determines effectiveness? Aust J Prim Health. 2015;21:391–408.

-

Sampson R, Barbour R, Wilson P. The relationship between GPs and infirmary consultants and the implications for patient care: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17(45):one–12.

-

Aguirre-Duarte NA. Increasing collaboration between health professionals. Clues and challenges. Colomb Med. 2015;46(2):66–70.

-

Schreiner A, Zhang J, Mauldin PD, Moran WP. Specialty referrals: a instance of who you know versus what you know? Abstracts from the 2016 Club of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting (JGIM) 2016;S402–3.

-

Hartveit Thou, Vanhaecht Thou, Thorsen O, et al. Quality indicators for the referral procedure from main to specialized mental wellness care- an explorative study in accord with the RAND ceremoniousness method. BMC Wellness Serv Res. 2017;17(4):1–13.

-

Tandjunga R, Hanharta A, Bärtschib F, et al. Referral rates in Swiss main care with a special accent on reasons for meet. Swiss Med Wkly. 2015;145:w14244.

-

Davies P, Puddle R, Smelt G. What exercise we actually know about the referral process? Br J Gen Pract. 2011;61(593):752–3.

-

Mota P, Selby Yard, Gouveia A, et al. Hard patient–medico encounters in a Swiss academy outpatient clinic: cross- sectional study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(one):e025569.

-

Duchesne S., Haegel F. L'enquête et ses méthodes. L'entretien collectif. Armand Colin Editeur. Paris. 2014; 35–94 French.

-

Kitzinger J, Marcová I, Kalampalikis Northward. Qu'est-ce que les focus groups? Bulletin de psychologie 2004;57(iii)/471:237-243. French.

-

Bowling A. Inquiry Methods in Health: Investigating Wellness and Wellness Services. 4th Edition. New York, U.s.a.: Open University Press. Mc-Graw Hill Education. 2014:410–418.

-

Kitzinger J. Introducing focus groups. BMJ. 1995;311:299–302.

-

Thorsen O, Hartveit M. Johannessen, et al. typologies in GPs' referral practice. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17(76):1–vii.

-

Malterud K. Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet. 2001;358:483–eight.

-

Pope C, Mays Northward. Reaching the parts other methods cannot accomplish: an introduction to qualitative methods in health and wellness services research. BMJ. 1995;311:42–5.

-

Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Qualitative enquiry in health care. Analysing qualitative data. BMJ. 2000;320:114–6.

-

Ayalon L, Karkabi K, Bleichman I, et al. Barriers to the handling of mental illness in primary care clinics in Israel. Admin Political leader Ment Health. 2016;43(2):231–40.

-

Akbari A, Mayhew A, Al-Alawi MA, et al. Interventions to amend outpatient referrals from principal care to secondary intendance. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;viii(four):CD005471:1–58.

-

Alber Chiliad, Kuehlein T, Schedlbauer A, Schaffer South. Medical overuse and quaternary prevention in master intendance - a qualitative written report with full general practitioners. BMC Fam Pract. 2017;18(99):one–xiii.

-

Bare L, Baxter S, Wood HB, et al. Referral interventions from main to specialist care: a systematic review of international bear witness. Br J Gen Pract. 2014;64(629):765–74.

-

Herrington P, Bakery R, Gibson SL, Golden Due south. GP referrals for counselling: a review and model. J Interprof Care. 2003;17(3):263–71.

-

Gandhi TK, Sittig DF, Franklin G, et al. Advice breakdown in the outpatient referral process. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(nine):626–31.

-

Barnett ML, Keating NL, Christakis NA, et al. Reasons for choice of referral dr. among master care and specialists physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;27(v):506–12.

-

Thorsen O, Hartveit M, Baerheim A. The consultants' role in the referring procedure with general practitioners: partners or adjudicators. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14(153):one–v.

-

Balint M. The crisis of medical practice. Am J Psychoanal. 2002;62(ane):vii–15.

-

Morgan DJ, Leppin AL, Smith CD, Korenstein D. A practical framework for understanding and reducing medical overuse - conceptualizing overuse through the patient-clinician interaction. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(5):346–51.

-

Balint Thousand. The doctor, his patient and the illness. Lond. 2000;1957.

-

Thorsen O, Hartveit Yard, Baerheim A. General practitioners, reflections on referring: an asymmetric or not-dialogical process? Scand J Prim Health Care. 2012;thirty:241–half-dozen.

-

Hoffmann TC, Del Mar C. Clinicians' expectations of the benefits and harms of treatments, screening, and tests: a systematic review. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(three):407–19.

-

Laine C, Turner BJ. The good (gatekeeper), the bad (gatekeeper), and the ugly (state of affairs). J Gen Intern Med. 1999;fourteen(five):320–1.

-

Pearson SD. Principles of generalist–specialist relationships. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;fourteen(Supp ane):S13–20.

-

Launer J. Collaborative learning groups. Postgrad Med J. 2015;91(1078):473–four.

-

Donohoe MT, Kravitz RL, Wheeler DB, et al. Reasons for Outpatient Referrals from Generalists to Specialists. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(5):281–half dozen.

-

Vannotti M. Le métier de médecin, entre utopie et désenchantement. Médicine et Hygiène, Chêne-Bourg 2006;82-93. French.

-

Albertson GA, Lin CT, Kutner J, et al. Recognition of patient referral desires in an academic managed care programme: frequency, determinants, and outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;fifteen(4):242–7.

Acknowledgements

We give thanks all the GPs who participated in this research and the Center for Primary Care and Public Health (Unisanté) for its authoritative support. Special thanks to Dr. Philippe Staeger, Dr. Alexandre Gouveia and Dr. Roane Keller for their communication and guidance. They gave permission for using their full names under the heading "Acknowledgements".

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KT conceived the written report, participated in the blueprint of the written report, conducted the analyses and drafted the manuscript. PNO participated in the design of the study, conducted the analyses, and amended the manuscript. RMV conceived the written report, participated in the design of the study and commented the manuscript. CB participated in the design of the study, developed the methodology for the study and amended the manuscript. NS participated in the design of the study and commented the manuscript. FS carried out the interviews, conceived the study, participated in the design of the study, and amended the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ideals declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was submitted to the Cantonal Commission on Ethics for Research on Human being Beings (CER-VD). The demand for consent was waived by the CER-VD, deemed unnecessary according to national regulations. More precisely, the Commission stated that our research project did not fall inside the telescopic of the Federal Law on Human Research as no personal wellness-related data would be collected or transmitted (FLHR, article two).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors have nothing to disembalm.

Additional data

Publisher'due south Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open up Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/four.0/), which permits unrestricted employ, distribution, and reproduction in whatsoever medium, provided you lot give appropriate credit to the original writer(due south) and the source, provide a link to the Artistic Commons license, and point if changes were made. The Creative Eatables Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/aught/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

Well-nigh this article

Cite this commodity

Tzartzas, K., Oberhauser, PN., Marion-Veyron, R. et al. General practitioners referring patients to specialists in tertiary healthcare: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract 20, 165 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-019-1053-1

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-019-1053-1

Keywords

- General practitioner

- Referral process

- Qualitative research

- Primary care

- Tertiary healthcare

What Two Data Elements Should Be Reported Because A Referral Is Involved,

Source: https://bmcprimcare.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12875-019-1053-1

Posted by: martincouseed1937.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Two Data Elements Should Be Reported Because A Referral Is Involved"

Post a Comment